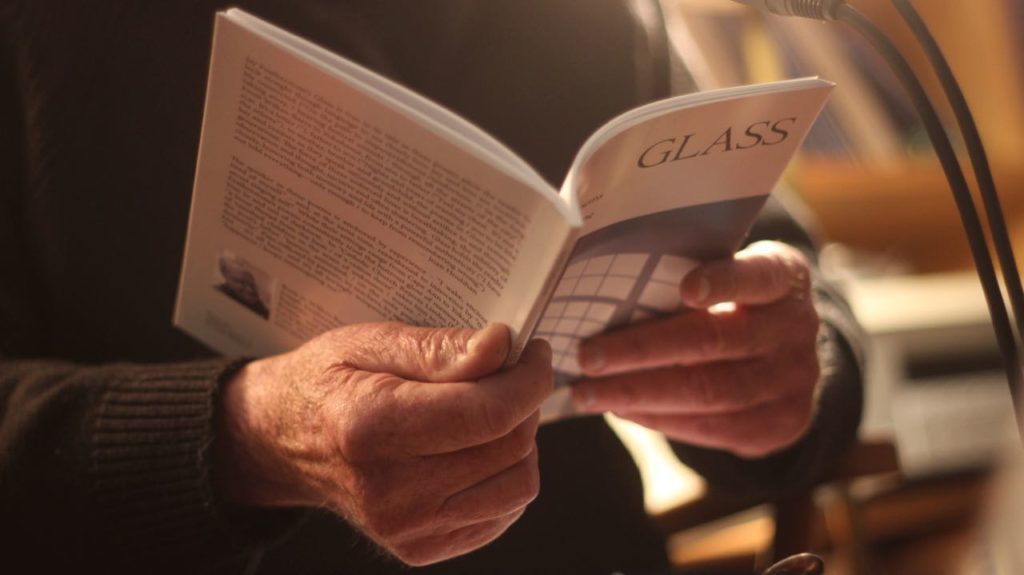

Jay Featherstone’s Glass is true to its title as these poems allow the reader to look straight though language to see clearly how joy and loss are inextricably connected (“On the path to impoverishment,/tenderness. // In the long taking away, / hearing festival sounds / through all the streets of the city.”). From Wilkes-Barre to Yokohama, from son to father (“Feel my chest. It’s not a scar. It’s a letter /”), father to son (“Nights and years of wanting / you to be like the others.”), to mother, brother and grandchild, the poems in Glass remember and conjure as they speak intimately and without artifice to and through generations. The force of these unforced lines is breathtaking, the subtlety of observation and thought, incisive and often shattering. Glass holds the reader closely, honoring both memory and life with a powerful authenticity (“I have not told everything—only enough / to keep from remembering wrong.”)

Joan Houlihan

The speaker in these poems is anchored by experience – “I wake, ancient, tired of myself” – and, at the same time, reawakened to innocence by “the secret singing self.” While their settings range from Cape Ann to Yokohama, Featherstone’s poems consistently trust the lustrous glow of memory to lead him in and out of darkness. In “Catholic Church Rejects Limbo (Reuters),” “a loose thread from the hem / of a cotton dress” takes him to “the vast rim of vanished children in the arms of unknown / nurses…” In “Bodhisattva,” the poet’s father “hovers, uninvited, / on the unlit porch /of my brother’s dementia.” Pain inflicted by parents, by teachers, by age, by love, by history, by fate – it’s all here, and it’s all lovingly tempered by a poet who confesses, “happiness / keeps interrupting me.”

Erica Funkhouser